Anatomy of a Volcano

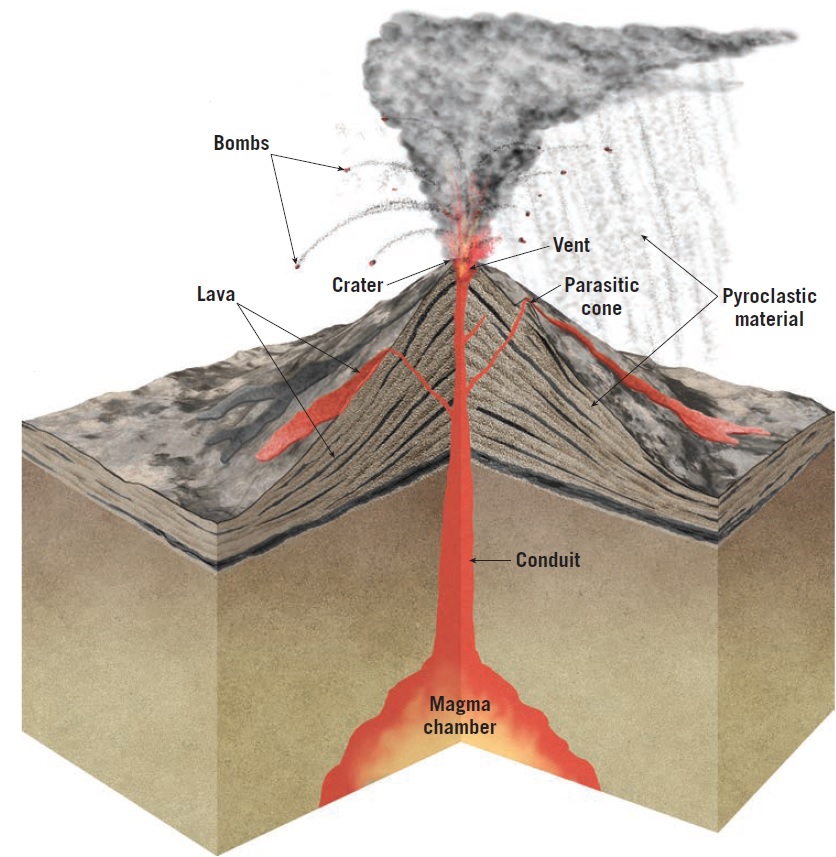

The anatomy of a volcano consists of several important parts of a volcano such as: magma chamber, conduit, vent, crater, you can see the detailed anatomy of a volcano below. But first, we will find out what a volcano is?

What is a volcano?

A volcano is simply an opening in the Earth’s surface in which eruptions of dust, gas, and magma occur; they form on land and on the ocean floor. The driving force behind eruptions is pressure from deep beneath the Earth’s surface as hot, molten rock wells up from the mantle. The results of this activity are a number of geological features, including the buildup of debris that forms a mound or cone commonly thought of as a volcano.

Anatomy of a Volcano

The popular image of a volcano is a solitary, graceful, snowcapped cone, such as Mount Hood in Oregon or Japan’s Fujiyama. These picturesque, conical mountains are produced by volcanic activity that occurred intermittently over thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of years. However, many volcanoes do not fit this image.

Cinder cones are quite small and form during a single eruptive phase that lasts a few days to a few years. Alaska’s Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes is a flattopped ash deposit that blanketed a river valley to a depth of 200 meters (650 feet). This event lasted less than 60 hours yet emitted more than 20 times the volcanic material of the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption.

Volcanic landforms come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, and each volcano has a unique eruptive history. Nevertheless, volcanologists have been able to classify volcanic landforms and determine their eruptive patterns.

In this section we will consider the general anatomy of an idealized volcanic cone. We will follow this discussion by exploring the three major types of volcanic cones—shield volcanoes, cinder cones, and composite volcanoes—as well as their associated hazards.

Volcanic activity frequently begins when a fissure (crack) develops in Earth’s crust as magma moves forcefully toward the surface. As the gas-rich magma moves up through a fissure, its path is usually localized into a somewhat circular conduit that terminates at a surface opening called a vent.

The cone-shaped structure we call a volcanic cone is often created by successive eruptions of lava, pyroclastic material, or frequently a combination of both, often separated by long periods of inactivity.

Located at the summit of most volcanic cones is a somewhat funnel-shaped depression, called a crater (crater = a bowl). Volcanoes built primarily of pyroclastic materials typically have craters that form by gradual accumulation of volcanic debris on the surrounding rim.

Other craters form during explosive eruptions, as the rapidly ejected particles erode the crater walls. Craters also form when the summit area of a volcano collapses following an eruption. Some volcanoes have very large circular depressions, called calderas, that have diameters greater than 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) and in rare cases can exceed 50 kilometers (30 miles). The formation of various types of calderas will be considered later in this chapter.

During early stages of growth, most volcanic discharges come from a central summit vent. As a volcano matures, material also tends to be emitted from fissures that develop along the flanks (sides) or at the base of the volcano. Continued activity from a flank eruption may produce one or more small parasitic cones (parasitus = one who eats at the table of another). Italy’s Mount Etna, for example, has more than 200 secondary vents, some of which have built parasitic cones. Many of these vents, however, emit only gases and are appropriately called fumaroles (fumus = smoke).