Where are diamonds found?

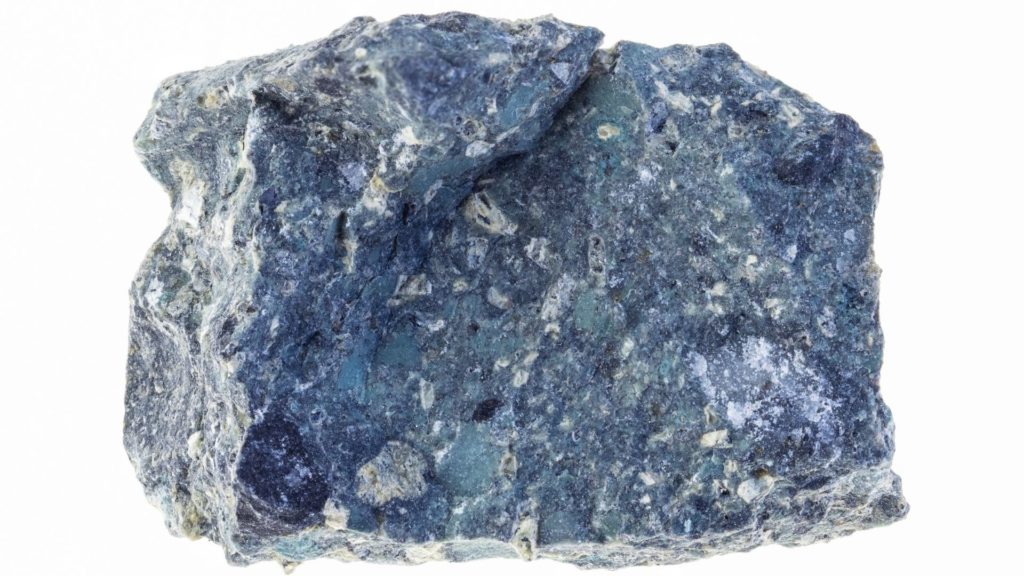

Diamonds are usually found in pipes (“diatremes”) in which certain Precambrian rocks exist. In general, these pipes are composed of an igneous rock called kimberlite – named after Kimberley, South Africa, where it was first discovered-an unusual rock made up of olivine, serpentine, mica, ilmenite, carbonates, and other minerals.

Diamonds are most often found in rock that includes the kimberlite matrix, fragments of both or one of the rocks called eclogite (mostly garnet and pyroxene) and peridotite (of the variety harzburgite, mostly made of olivine and pyroxene), and chunks of sedimentary or local rock. Most kimberlite pipes are shaped like an upside~down ice cream cone and were former volcanoes.

But kimberlite is not the only place to find these gems. Diamonds from the world’s most productive mine, the Argyle mine in western Australia, are found in lamproite, which is a close relative of kimberlite but richer in aluminum, potassium, silicon, and fluorine, and including less carbonate minerals. The shape of underground lamproite differs, too. Its upper extremes are wider where magma rose through the narrow pipes and came explosively into contact with cool, near~ surface groundwater.

Diamonds also occur in secondary deposits, such as in sands and gravels that are a result of erosion of kimberlite or lamproite. Sources of these types of diamond deposits occur in India, Namibia, and Brazil.

Where are major diamond deposits found?

Diamonds were first found as secondary deposits-sands and gravels from erosion and deposition of diamond-bearing rock-in India over 2,000 years ago. (Diamonds were first discovered in that country around 600 B.C.E.) By 1730, Brazil also became known for its diamonds that were also found in secondary deposits. It was not until the 1870s that South Africa became known for diamonds from the now-famous kimberlite mines. Russia (1950), Botswana (1966), Australia (1979), and Canada (1991) all became diamond producers, too. Currently, over 20 countries produce more than 110 million carats of diamonds each year.

Do some diamonds come from space?

Yes, scientists have discovered that some diamonds come from space, but don’t start looking for them to rain from the sky. These space diamonds are microscopic and come from certain meteorites discovered on Earth. One in particular is the Murchison meteorite, a space rock that contains minute diamonds around 4.5 billion years old. Scientists would love to discover more such meteorites, as these diamonds contain the isotopic (radioactive) “fingerprints” of the exploding stars that originally tossed them into space.

What are black diamonds?

Brazilian diamond hunters made an astounding discovery in the 1840s: rare black diamonds they called carbonados, the Portuguese word for “burned” or “carbonized.”

(Other carbonados have since been found in central Africa.) Unlike the single-crystal diamonds we are all familiar with, black diamonds are aggregates of individual crystals, giving the gemstone its dark color.

These coal-looking diamonds are over 3 billion years old, but no one knows how they originated. Some scientists believe they came from earthly organic carbon sources, similar to all diamonds found on Earth. But there is a definite problem with that idea: There were not enough organisms on Earth 3 billion years ago to form a carbon deposit, much less a diamond. Tn addition, chemical analysis of the carbon in the black diamonds shows they resemble surface carbons, unlike most diamonds forged deep in the Earth.

Because of the organic and crustal conundrum, other scientists believe these diamonds are from outer space, where a place in which carbon has been detected under many circumstances. Theories vary, but some believe the pressures from impacting space bodies (such as comets, asteroids, or other early planetary debris) could have carried the necessary carbon and created enough heat and pressure to form these diamonds.

What are the largest diamonds found to date?

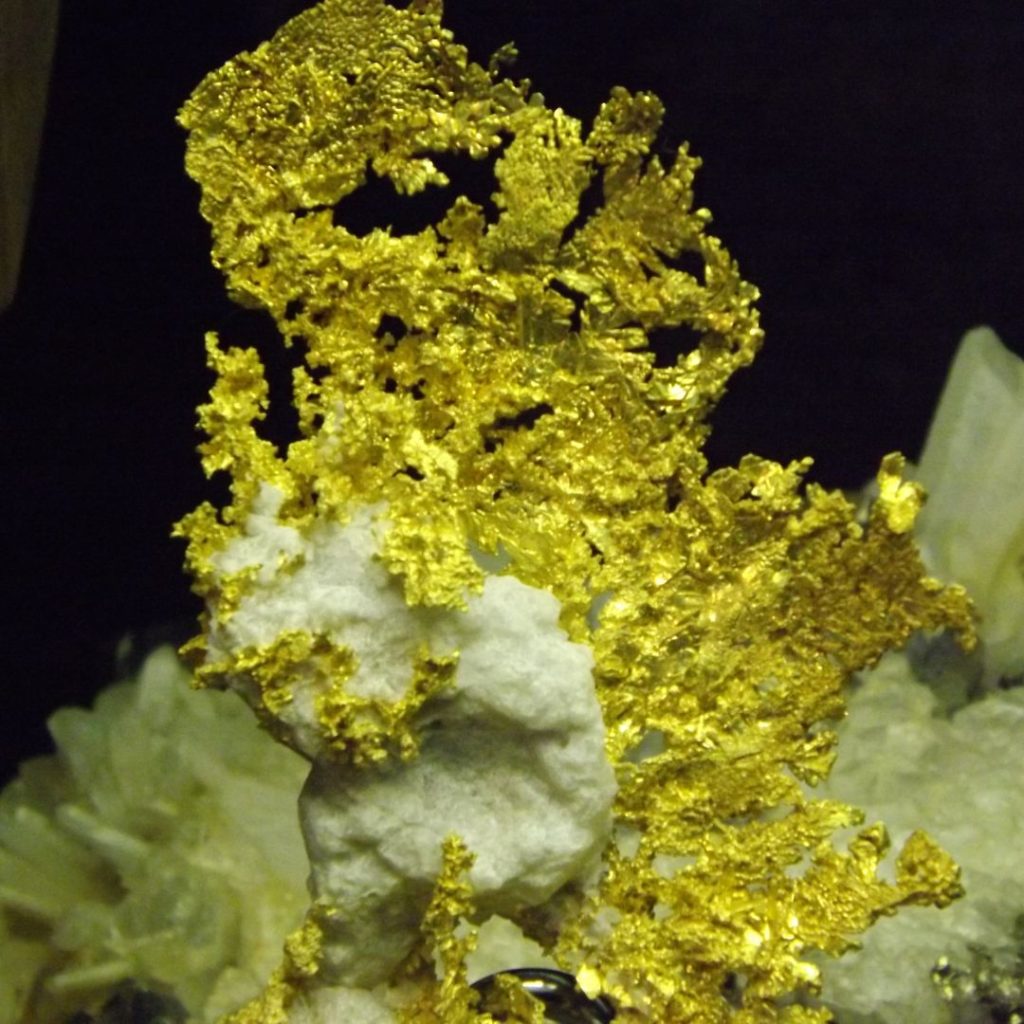

The largest cut diamond in the world is the Cullinan I, also known as the Star of Africa, weighing in at around 520 carats with 74 facets. It was cut from the largest rough diamond ever found the Cullinan- that weighed over 3,106 carats (over 1.25 pounds). In 1908, a diamond cutting firm cut the Cullinan I and 104 other diamonds from the original rough stone. Today, the Cullinan I sits in the Tower of London, set in the scepter of King Edward VII.

The second largest diamond ever found was the Excelsior, which in the rough originally weighed about 995 carats. It was found by an African mine worker as he loaded his truck. (His mine manager rewarded him with money, a horse, and a saddle.)

The original stone was cut into ten pieces; those pieces were in turn cut into 21 gems weighing 1 to 70 carats. The third largest rough diamond ever found was the Star of Sierra Leone, weighing about 969 carats; the fourth largest, the Great Mughal (often seen as Mogul), weighing about 793 carats, was named after Shah Jehan, builder of the Taj Mahal.

What are some famous diamonds?

Some of the most famous diamonds are not the biggest. For example, the Blue Hope (or Hope) diamond, weighing about 46 carats, was once owned by French king Louis XIV. Officially called the “blue diamond of the crown,” it was stolen during the French Revolution. It showed up again in 1830 and was bought by London banker Henry Philip Hope. Like the “curse of the mummy,” there is also believed to be a curse on this stone because bad luck seemed to follow many family members of the diamond’s owners (in reality, the reports of poverty, deaths, and suicides were probably due to the owners’ and families’ own doing, not a curse). The deep-blue, emerald-cut diamond became the property of the Smithsonian Institution in 1958.

Another famous diamond is the Koh-I-Noor (“Mountain of Light”), which weighs about 186 carats and was one of the large diamonds ever found. This gem has had a long and controversial history. It was first mentioned in records around 1304, when it was acquired from an Indian family that had allegedly owned the stone for generations.

Another account places the origins at 1526, when it was mined near the Krishna River. Still a different report has the gem adorning the peacock throne of India’s Shah Jehan in the 1600s. Its later history is more clear: After being stolen from India in the mid-1700s, it was taken to Iran, acquired by the Afghans, and finally lost to Indian rulers over a span of just under a century. When India came under British rule in 1849, the diamond’s travels were over: It was recut down to a “mere” 108 carats to enhance its brilliance during the reign of Queen Victoria, and now forms part of the British Crown Jewels.

There are also diamonds with a mythical background. But, like all legends, few people know the real story. For example, the pear-shaped Idol’s Eye diamond (weighing about 70 carats) gets its name from its legendary origin: The Sheik of Kahmir stole the diamond from an idol’s eye to pay his daughter’s ransom to the Sultan of Turkey. And like all long-term histories, there are diamonds with confounding backgrounds. One such diamond is the Sancy, the confusion being that another diamond had that same name.

What is the difference between precious and semi-precious stones?

Precious stones (or gems) are considered to be the most valuable gemstones and are the most rare and physically hardest. Diamond, emerald, and ruby are considered precious stones. Semi precious stones are usually softer and less valuable, and thus not as rare as precious gems. For example, the mineral olivine has a semi-precious variety called peridot that can be cut and faceted like any other gemstone; jade, garnet, amethyst, citrine, rose quartz, tourmaline, and turquoise are all examples of semi-precious gems. There are two major exceptions to the rule: Because of their rarity, opals and pearls are considered to be precious, even though they are both physically soft.