How Geysers Work?

Geysers

Geysers are intermittent hot springs or fountains in which columns of water are ejected with great force at various intervals, often rising 30 to 60 meters (100 to 200 feet) into the air. After the jet of water ceases, a column of steam rushes out, usually with a thunderous roar. Perhaps the most famous geyser in the world is Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park.

The great abundance, diversity, and spectacular nature of geysers and other thermal features in Yellowstone undoubtedly was the primary reason for its becoming the first national park in the United States. Geysers are also found in other parts of the world, notably New Zealand and Iceland. In fact, the Icelandic word geysa, meaning “to gush,” gives us the name geyser.

How Geysers Work

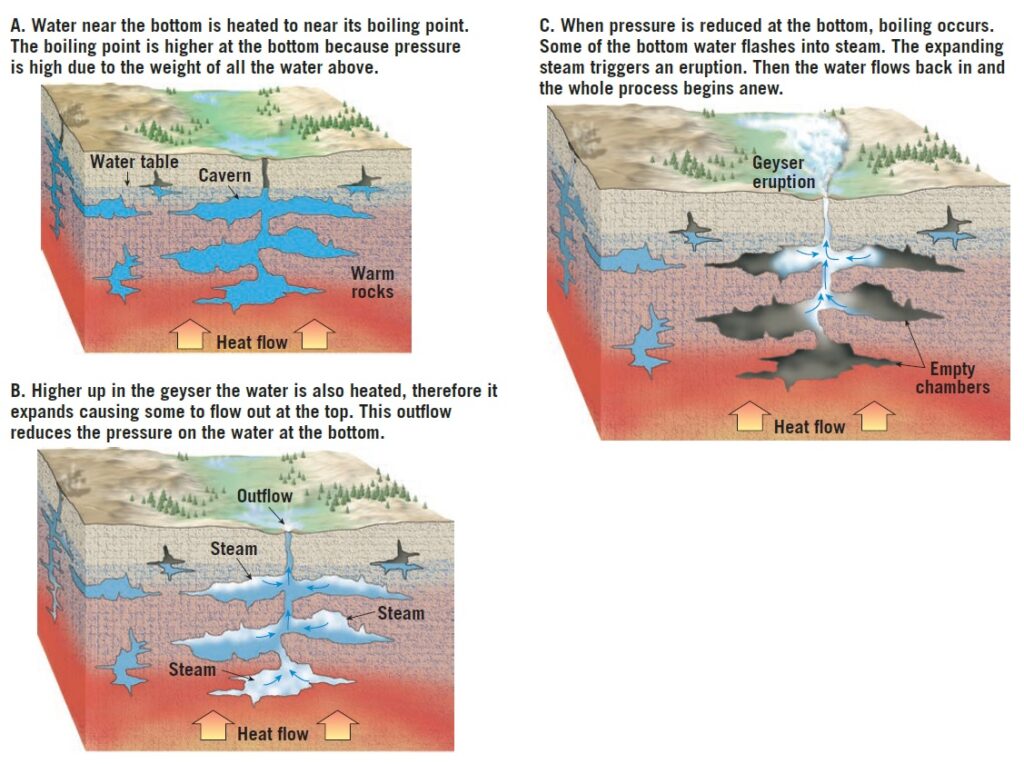

Geysers occur where extensive underground chambers exist within hot igneous rocks.

How they operate is shown in Figure 1. As relatively cool groundwater enters these chambers, it is heated by the surrounding rock.

At the bottom of the chambers, the water is under great pressure because of the weight of the overlying water. This great pressure prevents the water from boiling at the normal surface temperature of 100°C (212°F). For example, water at the bottom of a 300-meter (1000 foot) water-filled chamber must attain nearly 230°C (450°F) before it will boil. The heating causes the water to expand, and as a result, some is forced out at the surface. This loss of water reduces the pressure on the remaining water in the chamber, which lowers the boiling point. A portion of the water deep within the chamber quickly turns to steam, and the geyser erupts. Following eruption, cool groundwater again seeps into the chamber, and the cycle begins anew.

Geyser Deposits

When groundwater from hot springs and geysers flows out at the surface, material in solution is often precipitated, producing an accumulation of chemical sedimentary rock. The material deposited at any given place commonly reflects the chemical makeup of the rock through which the water circulated. When the water contains dissolved silica, a material called siliceous sinter, or geyserite, is deposited around the spring. When the water contains dissolved calcium carbonate, a form of limestone called travertine, or calcareous tufa, is deposited. The latter term is used if the material is spongy and porous.

The deposits at Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park are more spectacular than most others. As the hot water flows upward through a series of channels and then out at the surface, the reduced pressure allows carbon dioxide to separate and escape from the water.

The loss of carbon dioxide causes the water to become supersaturated with calcium carbonate, which then precipitates. In addition to containing dissolved silica and calcium carbonate, some hot springs contain sulfur, which gives water a poor taste and unpleasant odor. This is undoubtedly the case at Rotten Egg Spring, Nevada.